In 2020, 4,425 organ transplants were performed in Spain, according to the ONT (National Transplant Organization), which highlights that not even the COVID-19 pandemic has stopped this activity. But despite the fact that in our country we are leaders in the number of donors, there is still a lack of organs for patients who need them, and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that organ transplants carried out in the world do not they reach 10% of those that would be necessary, so scientists continue to search for a way to solve this problem.

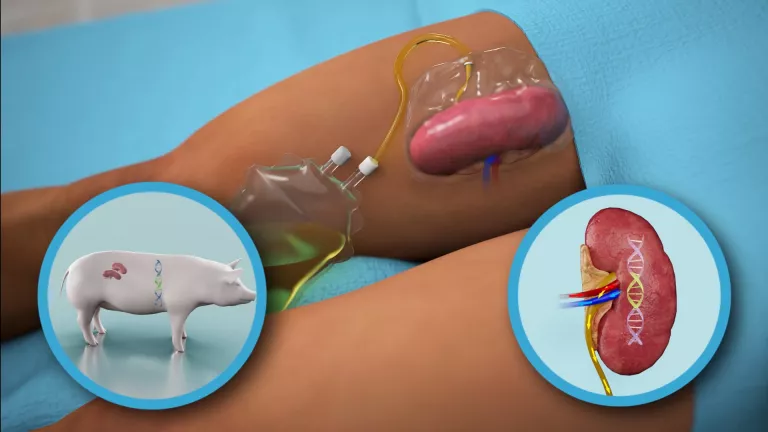

Xenotransplantation or heterologous transplantation (between different species) could be the solution if science manages to overcome the difficulties of compatibility that this procedure entails, because although a few weeks ago a pig kidney was successfully transplanted into a human for the first time, In this case, the word ‘success’ must be qualified, since the recipient was brain dead (the intervention was authorized by her relatives) and the kidney was functioning for a short period of time –54 hours–, at which time the investigators terminated the trial.

There are numerous antecedents of this historical milestone in which the receptor was not human, such as two carried out in primates: a pig kidney that worked for more than a year and a heart, also from a pig, that fulfilled its functions in another primate for more six months. In Spain, specifically in the Experimental Surgery Unit of the Juan Canalejo University Hospital, currently known as the University Hospital Complex of A Coruña, 20 kidney xenotransplantations were carried out from transgenic hDAF pigs (donor) to baboons (recipient) and, according to published data, xenograft survival ranged from 1 to 31 days.

How pig-to-human xenotransplantation was performed

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had authorized the pig kidney transplant to a brain-dead woman, whose family approved donating her body so that the intervention could be carried out. The donor animal, known as a GalSafe™ pig, was designed by Revivicor Inc. because it was necessary to remove the sugar molecule called alpha-gal, which is responsible for immediate rejection because the recipient’s anti-alpha-gal antibodies play a fundamental role in the deterioration of the transplanted organ. In addition, the pig’s thymus gland, which is responsible for educating the immune system, was transplanted with the kidney to prevent new immune responses to the pig’s kidney.

For xenotransplantation, a much more powerful immunosuppression would be necessary, with the complications that it entails in relation to the development of infections and tumors

The procedure was performed at the Kimmel Pavilion of New York University NYU Langone, in the United States, under the direction of Dr. Robert Montgomery, professor of surgery and chairman of the center’s Department of Surgery. The medical team attached the pig’s kidney to the blood vessels in the human’s leg in order to observe it and study its function.

They thus verified that both urine production and creatinine levels, which indicate a correct function of the organ, were normal and similar to what is observed in a human kidney transplant, and during the study period (54 hours) neither signs of rejection were detected. Dr. Montgomery has stated that his research “offers new hope for an unlimited supply of organs, a potential game-changer for the transplant field, and for those who now die for lack of an organ.”

Challenges to make xenotransplantation a reality

Getting an organ from an animal to be transplanted into a person and to function normally without being rejected by their immune system would make it possible to meet the great demand for organs that cannot be covered with donations, since it would mean having an animal source ( pig) that would provide organs suitable for donation. However, this would have to face many difficulties.

In the opinion of Dr. José Luis Escalante Cobo, Transplant Coordinator at the Gregorio Marañón University Hospital in Madrid, there are two fundamental challenges to overcome. One of them is immunosuppression: “When an organ is transplanted from one human to another, an attack is produced by the person who receives the organ because we are designed to defend ourselves against organisms, microorganisms or organs that come from other individuals, and it is necessary to administer immunosuppressive drugs. This, taken to the field of xenotransplantation, makes a much more powerful immunosuppression necessary, with the complications that these levels of immunosuppression entail in relation to the development of infections and the possibility of developing tumors after a while of taking this medication. ”.

This, however, would not be the biggest problem, says Dr. Escalante. There is another obstacle that has slowed down the progress of this type of research and that is that “while the infections that can be generated in humans are widely known and can be combated in most cases, veterinary medicine is much less advanced. and we do not know what can happen when transferring to a human an organ from an animal that could carry an infection that is not well known in the animal world and that develops in the human, that is not adapted, or that lacks mechanisms of action and of rejection, which could lead to a disseminated infection, and even a pandemic such as that caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus; in other words, it would be getting into a field in which we would have to tread carefully because we would not only be endangering the recipient of the organs, but could also generate an infection potentially transmissible to people who were in contact more or less close with the patient, or even expand an infection to unknown limits”.

“We do not know what can happen when an organ is transferred from an animal to a human that could carry an infection that is not well known in the animal world and develops in humans”

The Gregorio Marañón Transplant Coordinator also points out that in medicine the risk-benefit balance is always taken into account, and for this reason he believes that the heterologous kidney transplant “has less chance of advancing, since exposing a patient to a kidney transplant with high risks to their safety would not be justified because we have an alternative, which is dialysis, while in other types of transplants such as heart, liver or lung transplants, in which the patient’s life is in serious danger, from the ethical and medical point of view, in some cases it could be justified to open a trial or a line of research”.

Dr. Escalante affirms that “in the end we will go to a personalized medicine or surgery, in which the organs have been genetically modified so that, on the one hand, the rejection response is less and they are better tolerated by those who receive them and, on the other, that those modifications also reduce or eliminate the possibility that they can transmit infections”. “But for that much more knowledge is needed from the point of view of infectology or infectious diseases in animals”, he concludes.

Dr. Rafael Máñez Mendiluce, Head of the Intensive Care Medicine Service at the Bellvitge University Hospital (Barcelona), who was responsible for transplants and research in this field at the Experimental Surgery Unit of the Juan Canalejo University Hospital, currently called the Hospital Complex University of A Coruña considers that “we are closer than ever (to xenotransplantation) if you want to try”, but if the authors of the trial carried out in the United States have not considered the jump to the clinic and replicate the procedure in living people , surely there will be aspects that have not been explained, or have been explained little, and that still cast doubt on whether these same results can be obtained in humans.

According to this expert, the fact that hyperacute rejection has not occurred is not new because 25 years ago it was verified in primates and it was known that, in principle, it would not occur in humans either. The main difficulties that arise, he points out, are the very powerful immunosuppression to which it is necessary to subject the recipient to avoid long-term rejection – “although we managed to reduce it a lot with genetic manipulations in the pig” -, which could have side effects important, and organ survival.

He explains that physiological aspects are also of great concern “especially in the case of organs that have complex physiological activities, such as the kidney, because in my time we already knew that pig erythropoietin did not work in humans.” “The other issue is the functionality of the organ. In this sense, the heart, in principle, would have to be the easiest to transplant because from a physiological point of view it is a muscle, while in the liver a multitude of proteins are produced, which are the ones that regulate 80-90% of the functions that the body carries out, so it is very difficult, or very unlikely, that we can get a pig liver to work indefinitely in humans.”

“The kidney is less complex than the liver, but it also produces a series of proteins and hormones, such as erythropoietin, which is responsible for producing red blood cells (erythropoiesis), and it would not make sense to also administer externally all these hormones because those of the pig are not going to work”. “There are, then, genetic conditions, which make it not so easy to do it,” he concludes.

However, the potential is incredible, as Dr. Montgomery states: “If science and experimentation continue to advance positively, we could be close to kidney xenotransplantation in a living human being. And the future of this work is not limited to kidneys. Transplanting hearts from a genetically modified pig may be the next big thing. This is an extraordinary moment that should be celebrated, not as the end of the road, but as the beginning. There is more work to be done to make xenotransplantation an everyday reality.”

.